Test of faith

Mainline Protestant churches across downtown Hamilton are in trouble. Declining congregations and revenue have put them in a fight for survival that could permanently alter the city’s religious and architectural heritage. Spectator reporter Teri Pecoskie reports on the creative steps many are taking to stay afloat before a key piece of the city’s history is lost forever

By Teri Pecoskie

Rev. Ian McPhee is blunt about his church’s lifespan.

“We have five years,” he says. As long as there are no surprises.

McPhee is flanking the fireplace in a cosy room at Erskine Presbyterian. He’s been the minister at the Pearl Street church, just north of King, for 23 years — long enough to become an authority on its past and apparently inevitable decline.

Built in 1884, the Strathcona landmark has always been blue collar, a place of worship for generations of plumbers, joiners, rail workers and their families who lived in the tidy neighbourhood.

After the First World War, there were 3,000 of them — more than three times what the church could hold. Today, there are fewer than 100, and Erskine’s once-healthy bequests are running low.

“People have left us money but that is obviously being eaten into,” McPhee says. “So we made a decision: We’re not going to just survive. If we have to go out in a blaze of glory, we will, but we’re going to do ministry, we’re going to be a church that reaches out.”

RELATED STORIES

Catholic Church continues to flourish

St. Vladimir has an interest in the future

The saga of St. Mark’s Anglican Church

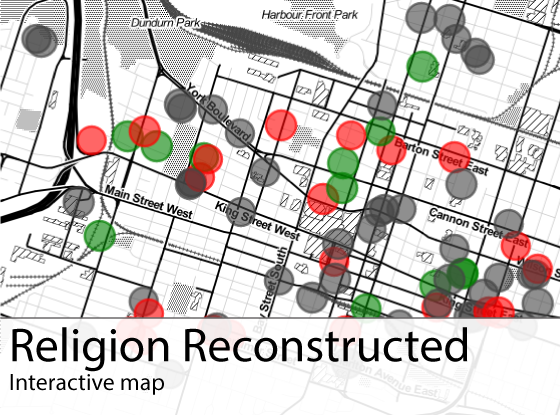

Interactive overview: Churches and congregations

McPhee isn’t alone. Across Hamilton, and particularly in the downtown core, so-called mainline Protestant churches are taking a hard look at their options — what, if anything, can they do to survive?

Declining membership is the central challenge, according to church leaders and the experts. Their buildings are also old and costly, and their reserves, like Erskine’s, are drying up.

In the last 20 years, more than a dozen have closed. Several more are on the brink of closure, taking creative steps, such as sharing space or selling their properties, to keep their congregations afloat.

It may be a losing battle.

“I think the writing is on the wall,” says Reginald Bibby, a University of Lethbridge sociology professor who studies religious trends. The mainline groups — Anglicans, Presbyterians, Lutherans and the United Church — will, with a few individual exceptions, continue to shrink, “and with their related declines in resources, will see most of their physical outlets sold off.”

Many of these churches will be bought by developers. Some, like James Street Baptist, will be transformed, while others, like All Saints Anglican, will be rebuilt.

Aging out

The vast age differences between Canadians who identify with a particular religion offers a clue as to why some groups are shrinking and others growing.

Here’s a look at the median age of the country’s faithful, according to a recent Statistics Canada report:

Muslim: 28.9

Sikh: 32.8

Hindu: 34.2

Roman Catholic: 42.9

Anglican: 51.1

United: 52.3

Still others will simply be razed, permanently altering the city’s religious and architectural heritage. Not the Catholic churches, though. Interestingly, that faith has a larger following in Hamilton than ever.

“The mainline groups themselves will probably never die out altogether, but will constitute minor players on the Hamilton and Canadian religious scenes,” says Bibby. “As such, they will be relegated to history, locally and nationally — their few remaining structures serving as memories of something that once was.”

In the wake the Second World War, mainline congregations were booming in Hamilton. More than a dozen new churches were erected and membership, too, was on the rise.

After peaking in 1971, however, the numbers have run almost exclusively in one direction: down.

According to Canada’s National Household Survey, the number of Anglicans in the Hamilton metropolitan area, which includes Burlington and Grimsby, dropped 41 per cent between 1971 and 2011, while the United, Presbyterian and Lutheran churches experienced even greater losses.

At the same time, the number of Roman Catholics, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and Muslims has grown significantly, due mostly to immigration. So has the number of those with no religious affiliation.

These trends aren’t limited to Hamilton, says David Seljak, an associate professor and chair of the religious studies department at St. Jerome’s University in Waterloo. In fact, the booms and busts are well documented from coast to coast.

“There is no place where the mainline Protestant churches are not in a steady state of decline,” he says. “It’s something that is happening across Canada and it has been happening for some time.”

While the numbers may paint a simplistic picture of religious change in Hamilton and elsewhere, the reasons for these shifts are complex. In broad strokes, though, it comes down to social change — everything from shifting immigration patterns to our movement to a seven-day-a-week, individualistic consumer culture — and the failure of churches to adapt.

“The forces moving people out of churches are much bigger than the churches themselves,” says Seljak. “People are pursuing spiritual goals, but not in the traditional organized religion that the church is.”

MacPhee, the Erskine minister, agrees.

[“I] think people are spiritual, but not religious,” he says. “I believe people are still searching for meaning and purpose and community, but churches are probably the last places they would go because they have either been burned or their parents have been burned or they just find it irrelevant.”

Fresh starts

Since 2000, no less than 20 new religious institutions have been established in Hamilton — half of which are either Pentecostal or non-denominational. Here’s a list of the recent openings:

Eucharist Church, Sheffield Meditation Centre, Iglesia Pentecostal Hispana de Canada, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Providence Canadian Reformed Church, Lift Church, Centro Internacional de Adoracion, St. Mary the Virgin, Divine Light Awakening Mission, Restoration House Hamilton, All Saints of North America Orthodox Church, Polish Full Gospel Church, First United Pentecostal Spanish, Covenant Canadian Reformed Church, Meadow Creek Community Church, Le Centre Chretien Beth-Eden, Trinity Canadian Reformed Church, Apostolic Ark Ministries

It’s not just mainline, or even Christian churches, experiencing the blowback. Hamilton’s mosques and temples are feeling the effects of anti-institutionalism too, even though it’s not borne out by the numbers.

Consider Hamilton’s Muslim population, which has climbed 1,200 per cent in the area since 1981. Yet mosques are still concerned with declining attendance because young Muslims are seeking something more.

“The immigrants want to replicate what I call the immigrant Islam phenomenon,”says Liyakat Takim, McMaster University’s Sharjah Chair in Global Islam. “Whatever kind of Islam they used to practice abroad, whether it’s Pakistan, India or the Middle East, they basically want to do things the same way they did there.

“But the younger generation is kind of looking for something different, to de-ritualize religion, so to speak.”

Seljak describes this movement as a “strong current” in Canadian culture. It’s pushing people toward individual spiritual seeking and away from traditional religious communities, and not a single denomination — from Buddhism to Baha’i — is safe.

“The actual way they’re being religious is changing,” he says.

If local churches can’t find a way to either fill pews or compensate for shrinking congregations, the consequences could be dire from a social as well as an architectural standpoint.

That’s because with fewer people comes fewer resources — resources necessary for things like community outreach and ministry, as well as church infrastructure itself.

“In Hamilton, like the rest of Ontario, you’re going to see these communities, especially the mainline Protestant churches, more and more pressed for money. As a consequence, there’s no way they can keep these churches open any longer,” Seljak says. “If they don’t start adapting soon, it will be the case that they will disappear.”

The problem is particularly pronounced on the fringes of the city and downtown, where big, century-old buildings make up a significant chunk of the church stock.

[S]o what will they do when the money runs out?

It’s a question Rev. Cathy Stewart has been grappling with for two years.

Mega churches

Most, but not all, of Hamilton’s religious institutions have experienced a decline in membership over the last 30 years. In fact, a few are bursting at the seams. Here’s a look at the city’s five most populous institutions as well as their rates of growth since 1984:

St. Margaret Mary

Congregants: 13,994

Growth: 224 per cent

St. Francis Xavier

Congregants: 13,750

Growth: 72 per cent

Our Lady of Lourdes

Congregants: 10,500

Growth: 207 per cent

Our Lady of the Assumption

Congregants: 10,239

Growth: 105 per cent

St. Demetrios, Greek Orthodox

Congregants: 10,000

Growth: 100 per cent

Stewart, the minister at MacNab Street Presbyterian, knows it’s impossible to maintain the 1854 church with its current revenues. And like Erskine, the community is already tapping into its trust.

It’s the same story at most of the big churches in the core, she says. “It feels like we’re heading toward a fiscal cliff.”

Stewart can’t say exactly how long her 230-member congregation has left, but she knows the end is near. Near enough, anyway, to talk about options.

Her church — a hulking grey stone and stained glass structure just south of the tracks by city hall — is beautiful, but costly. Heating the building is a massive expense.

“What do you do,” she says, “when the congregation can’t afford to keep that up?”

There are dozens of examples across the city where churches are taking steps — in some cases, bold ones — to adapt to the new realities of religious life.

Some, like Centenary and St. Giles United, have chosen to amalgamate, merging two distinct congregations into one. Their newly formed church, One Main Street United, has yet to settle on a single home base, and is working with EDGE, a United Church of Canada program, to come up with a plan for its more than 100-year-old buildings at 24 Main St. W., and Holton Avenue at Main Street East (see sidebar).

Others are sharing space with community groups, or even other denominations, as a means of making ends meet — something experts say wouldn’t have happened when mainline churches were at their peak.

“They’ve all taken on this kind of multiple role,” says Ranu Basu, a geography professor at Toronto’s York University. “They’ve become places where diversity meets, interacts and is able to form these kind of really, really interesting communities.”

(Listen: Lee Beach, an assistant professor of Christian ministry at McMaster Divinity College, on the future of the lower city’s aging church stock.)

In a few instances, communities such as James Street Baptist deconsecrate and off-load their aging properties. That church, now Graceworks Baptist, sold its 130-year-old landmark building at the corner of James South and Jackson in 2012. Today, congregants gather for Sunday service in The Spectator’s Frid Street auditorium.

Still others are taking on development themselves — renovating, severing or building onto existing space and marketing it for commercial or residential use.

[T]hese strategies are both brand new and as old as the church, says Seljak, the St. Jerome’s professor — just the latest in a series of ways institutions have adapted to change over the centuries, to feudalism, absolute monarchy and, now, to consumerism.

“It just goes to show you which way the wind is blowing, who has the power in society,” he says. “It’s the businesses and corporations. It’s not the church anymore.”

In Hamilton, the Anglican Church is especially eager to capitalize on capitalist culture. It recently invested in a major renovation at Church of the Ascension, relocating the kitchen, offices and hall to the church proper, so it could sever or lease the rest of the 160-year-old Forest Avenue building. Ten blocks away, at Christ’s Church Cathedral on James North, plans for a new development are also under way.

“We can’t afford to maintain this place forever on the amount of money it’s costing us,” says the Very Rev. Peter Wall, the cathedral rector and dean of the Anglican Diocese of Niagara. “The only way we can do that is to do something that contributes to the sustainability of this place and allows us to have a greater impact on the community.”

Since Wall arrived at the Cathedral in 1998, the number of Anglicans in the Hamilton area has declined more than 23 per cent. His church alone has lost about 50 families in the past 30 years.

Though Wall is mum on the details of the development, he says he’s committed to maintaining the integrity of the mid-19th century gothic cathedral — a soaring stone structure with heritage designation inside and out. Still, the church must innovate if it wants to survive.

“God is not inside that building,” he says. “We don’t have to tiptoe in and say, ‘where is he?’ and look under all the pews.

“That’s bad religion, that’s hocus-pocus, that’s nonsense. And that’s what killed the church.”

Commercialization is just the latest tack taken by churches in an attempt to adapt to social change. And the shift, like those before it, could have a major effect on the way the masses experience religion.

Take Christianity, says Seljak. As the religion spread to Rome in the fourth century, it became much less friendly to women because Roman society was much less friendly to women.

[J]ust like today, Christianity was adapting to the times.

“The type of society you operate in always changes the religion and distorts it,” he says. “In this case, the distortion would come from the commodification of religion.

“If religion becomes another consumer product that people consume the way they do, say, world music, then the experience can risk becoming quite shallow.”

That’s not the only drawback. A slice of local history will also be lost as churches are sold off, developed or torn down.

Look at a city such as Houston, says Seljak. Over the last century, the Texas metropolis demolished much of its historic infrastructure and erected shiny skyscrapers in its place.

What you have now is a city “with no sense of its history,” he says. And without that, “you have no sense of where you’ve been.

“You lose your sense of where you are now and where you are going,” he adds. “It can be very disorienting.”

Diane Dent, the longtime president of the Heritage Hamilton Foundation, agrees.

“When you drive through Quebec you see all the church steeples,” she says. “That’s historical perspective of past generations.

“What’s going to be our perspective of past generations here?”

Dent, a former French professor and part-time director of development at Redeemer University College, has fought to protect the city’s built heritage since she moved to the Durand neighbourhood in the 1960s. She’s since played a part in saving numerous downtown landmarks, including the Bank of Montreal building, the post office and the Lister.

When asked what the potential loss of Hamilton’s historic churches could mean for the city’s future, Dent is quick to answer.

“Devastation.”

The good news is that it could be avoided — in her view, through three steps: the creation of a national, provincial or regional policy to protect buildings of significance, mandatory designation and easement and, finally, adaptive reuse.

“You have to have a carrot and a stick,” she says. “If there’s the stick and you can’t demolish them, bright ideas will arrive.”

A living project

Over the last two years, The Spectator compiled demographic information on more than 450 religious institutions — including mosques, temples, churches and non-denominational organizations — across Hamilton. We then cross-referenced this data with information from National Household Surveys administered by Statistics Canada since 1961 to uncover broad trends for religious identification and church attendance in the city.

One of the largest challenges in carrying out this project is that few religious institutions maintained historic records of church attendance (we requested the congregation size 30 years ago and today, as well as information about changes of address, church mergers, major renovations and partnerships). There’s also no independent organization that tracks such information at a local level.

The consequence is that much of our data is self-reported. That means there was no way to independently verify the accuracy of some numbers and events.

On top of that, there were some areas in which institutions either didn’t respond or drew a blank.

If you think you can help fill in some of the missing pieces, please contact:

Teri Pecoskie, reporter

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 905-526-3368

Twitter: @TeriatTheSpec

She will ensure the information is added to this online resource, helping to better inform both our readers and our reporting of religion and religious trends in Hamilton.

Dent admits change won’t be easy. It also won’t be cheap.

“In these difficult times, you need someone who cares about heritage, who has deep pockets and is willing to buy up properties and restore them,” she says.

But who?

Developers aren’t exactly chomping at the bit to buy up churches, especially those with a heritage designation attached. And the city isn’t either — not after its experience with St. Mark’s, an old Anglican church at the corner of Bay and Hunter streets that it bought from the Diocese in 1994.

Since then, dozens of ideas have been floated to use the building for everything from city offices to a cultural programming centre. None, however, have officially taken flight.

“I don’t feel there’s any great appetite on council to scoop up these potential places of worship,” says downtown councillor Jason Farr. “I don’t see it as a priority.”

Instead, he believes private sector investment is the solution — one that could also help boost the coffers. In Canada, religious charities and communities are generally exempt from property taxes.

The challenge remains, though. It’s not an easy sell.

That’s because adapting churches for reuse is difficult and costly — much more so than, for example, overhauling an old school.

“When you have a steel structural frame, and, in many cases, poured concrete, you have a very robust building structure that is much easier to adapt,” says Drew Hauser, a principal with McCallum Sather Architects Inc. But a cavernous stone structure with three-layer wall systems — “that’s very challenging.”

That being said, it’s not impossible.

“Anything could be saved if you’ve got enough money,” says Hauser. “It has to make sense.”

905-526-3368 | @TeriatTheSpec

You must be logged in to post a comment.